Celebration

Maori Costume and Taniko

The 21st century has brought many adaptations and interpretations of Maori costume. While it is definitely feasible that the style of costume is evolving, many interpretations unfortunately demonstrate a lack of care and research into style and materials used for traditional costume. On the other hand, there are also very elegant interpretations that are dignified even without using traditional style or materials.

The costume outlined here is considered "traditional", but it is really a modern adaptation based on tradition. Taniko weaving and taniko designs used in the various costume pieces are the intended focus of this page.

Traditional costume is worn by members of concert groups (also known as kapa haka groups, cultural entertainers or theatre groups) at many different events around New Zealand, occasionally by guides who conduct visiting V.I.P's around the thermal areas of Rotorua, and at several destinations around the country dedicated to offering tourists an encounter with some form of Maoritanga. As well, kapa haka groups are often attached to ex-patriot associations, New Zealand Embassies, Consulates and trade missions in many parts of the world.

However, for important and ceremonial occasions Maori dignitaries and people such as the reigning monarch, selected Heads of State and people who have been awarded the entitlement to wear a kakahu (cloak), usually wear it over formal attire. Such kakahu are woven with authentic materials in the traditional manner, and are priceless artifacts in their own right.

FEMALE COSTUME

With the passage of time Maori costume has undergone several changes. The arrival of missionaries influenced the most significant change in traditional women's clothing, mostly for the sake of modesty and decorum as they saw it - the introduction of the pari for women.

Over the last hundred years or so more subtle changes have gradually been wrought. Around the time of Cook's arrival (1769) women wore a maro, a triangular shaped garment worn exactly like an apron. By the end of the 19th century the maro had gradually evolved into a kilt- or rapaki-like garment similar to the piupiu we know today but also included a cloak-like woven inner lining. That inner panel gradually became just a waistband and a much lighter weight cotton fabric underskirt called a panekoti (derived from the english word "petticoat") appeared. In general terms, women's garments have remained relatively unchanged since then. In modern times, the underskirt is usually red or black in colour, and attached to either the pari or piupiu in women's costume. It should correctly be the same length as the piupiu although there is a trend towards a longer underskirt with a printed design visible on the extention below the bottom of the piupiu. At some ceremonial events and occasions as well as cultural presentations, the piupiu may even be seen worn in a manner similar to a cloak, over regular street clothes (usually black dresses for women).

| Demonstrating a modern version of "traditional" female costume, the doll in the image (at left) is wearing a kahu huruhuru (feather cloak). Pari (bodice) and tipare (headband) are taniko woven. Two poi (balls on string) which are swung to music and song, are hanging from the waistband of her piupiu (flax skirt). On the doll's chin is a moko (tattoo); around her neck is a tiki pendant; in her right ear a kuru (straight drop pendant) made of greenstone (pounamu - the NZ nephrite jade) and in her left ear a mako shark's tooth. Feathers in the hair traditionally denoted rank in Maori society, and would have come from the prized Huia bird. Costume elements for males are discussed below. The Cabbage Patch(�) doll shown here was officially re-named "Rangimarie Moana" from her original given name. All items of her clothing were made by me, including piupiu and kakahu. She won First Prize at the Pacific National Exhibition in Vancouver in 1988. |

MALE COSTUME

While the female costume has remained fairly static for much of the last century or more, male costume has varied in style and garments over the years. Similar to the women's costume, maximum male costume would include a kakahu, either as a kahu huruhuru or the korowai with tags woven or attached to it, and in recent years cloaks made in the style of short rain capes seem to be appearing, as well. Neck and ear ornaments as described for women are also worn, and occasionally feathers, too.

Until the middle of the 20th century some piupiu worn by men were decorated with taniko weaving across top edge. Nowadays men's piupius are shorter (now mid-thigh) with a plain black woven or plaited top edge. For much of the century males wore a tapeka (body band, a.k.a. bandolier) diagonally across the chest but now there is a swing back to a style of costume that reflects the taniko woven decorative top edge on piupiu. Instead of the tapeka, which is no longer favoured, many male members of entertainment groups now prefer the tatua a wide type of belt worn around their waists over the plaited waistband of their piupiu. Like the tapeka or the women's tipare, the tatua is often patterned after the design on the woman's pari. Black shorts or a black bathing suit are now commonly worn by men for modesty and dignity.

Also popular with some groups, (particularly children's groups) in lieu of the flax piupiu for boys is a type of linen fabric wraparound kilt, called a rapaki, with thrums of black flax fibre attached randomly. This is based on a cloak-like garment that males wore around their waists in the pre- and early-contact periods. The tatua can be worn with the rapaki. While it could be considered more modest, and certainly more cost efficient for children's groups, it is a shame that male members of some entertainment groups are foregoing the traditional piupiu.

(As a small digression from the subject of this page, it needs to be noted nevertheless, that, although flax piupiu as they are known today have only been around for perhaps a hundred years or so, they are sadly being seen less and less for another reason. Cultural groups are turning more often to piupiu made of yarn and plastic tubing. With the rigourous demands of a cultural group's presentations, these modern piupius are indeed more durable and cost effective than those made of flax. While the heavier plastic tube piupiu behaves very similarly to the traditional flax piupiu the distinctive rustling and slapping sounds of the strands of flax as the wearer moves in dance or haka are being lost and forever silenced.)

TANIKO DESIGNS

Although taniko designs are still a prominent part of

Maori costume, only kakahu usually have authentic and

traditional taniko weaving incorporated into them. (Note the

kakahu in the photo at right - it is being worn with the taniko

design on the upper edge. While this is often seen,

strictly speaking it is incorrect. Taniko weaving is

traditionally found at the bottom edge of kakahu.)

Although taniko designs are still a prominent part of

Maori costume, only kakahu usually have authentic and

traditional taniko weaving incorporated into them. (Note the

kakahu in the photo at right - it is being worn with the taniko

design on the upper edge. While this is often seen,

strictly speaking it is incorrect. Taniko weaving is

traditionally found at the bottom edge of kakahu.)

Instead of using costly and time-consuming taniko weaving for pari and tipare, other techniques are often used today to create taniko designs. For example, cross stitched pari and tipare (as shown at right) are the most commonly seen, but other embroidery techniques may also be employed such as embroidery on canvas, ribbon or ric-rac embroidery, they might be tapestry woven, worked in machine applique, patchwork, screen printed or even simply painted.

Taniko designs that are indigenous to, or have special significance for, whanau , hapu and/or iwi, (extended family, sub-tribe and/or tribe) can often be seen on costumes worn during a cultural presentation or festival.

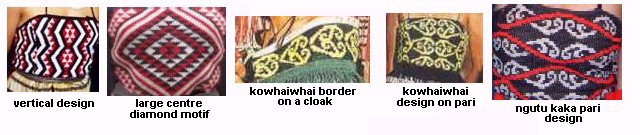

Designs for the pari can be worked in one of several different

styles. Some are based on a square or rectangular shape with the

dominant design motif worked in the centre front of the pari. Some

are based on multiple recurring diamond designs aligned vertically in the style of the whakarua kopito (two points) classification of taniko designs, and others are narrow horizontal design strips. Most often seen, however, is a pari design that includes a large single diamond shape in the centre front with a star-like motif (or similar) in the centre. Several different pattern elements can also be included in the designs, such as diamonds, triangles, solid bands of colour and perhaps a logo or a motif meaningful to the group. It is interesting to note that curvilinear designs are beginning to emerge as designs on pari and also as a taniko-style border on kakahu. Two particular designs, one named kowhaiwhai and the other ngutu kaka were both developed as knitting patterns in the late 1960s and published in a booklet by a New Zealand woman's magazine. Both designs are used as multiple horizontal bands across the width of the pari. Working from a chart, knitting designs can be easily re-interpreted in taniko weaving.

|

Another specific design that is also seen is the poutama pattern, or some sort of variation of this design. Known in English as the "Stairway to Heaven" and also the "Stairway of Knowledge", it is often used, appropriately, in costumes for school kapa haka groups, with the school logo or insignia included in the centre front motif. This is a very attractive style of pari for a school group participating in a competition, and suggests that care and attention to detail were taken into consideration when creating the costumes. |

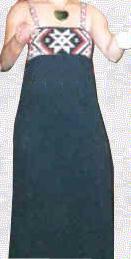

A costume style which seems to be popular at the moment is a sort of "hybrid" costume. I am not here to judge whether this is right or wrong, correct or incorrect, so this is just a brief discussion of one alternative costume that is currently being used. (A personal note - to be honest, although I prefer - and would recommend - the more traditional style of costume, I think this is actually a rather attractive outfit.) It is, ofcourse, taking the pari and attached (under)skirt one step further in the course of costume evolution. This particular style of outfit for a cultural group might appear in either red or black, as shown at right, and could also include karure or similar tags (not shown in this particular image) that are stitched to the body of the outfit in a uniform pattern. The decorative yoke is ideal for showcasing taniko designs that are significant or meaningful to the group. In the same way pari are created for the more traditional costume, the yoke, and indeed, even the shoulder straps may be woven, cross-stitched or decorated in an appropriate taniko design. Worn as a long dress, this style of costume is obviously a women's garment - male members of the cultural group wear normal costume as described above. Tipare on women, neck and ear ornaments and feathers in the hair may also be included.

A costume style which seems to be popular at the moment is a sort of "hybrid" costume. I am not here to judge whether this is right or wrong, correct or incorrect, so this is just a brief discussion of one alternative costume that is currently being used. (A personal note - to be honest, although I prefer - and would recommend - the more traditional style of costume, I think this is actually a rather attractive outfit.) It is, ofcourse, taking the pari and attached (under)skirt one step further in the course of costume evolution. This particular style of outfit for a cultural group might appear in either red or black, as shown at right, and could also include karure or similar tags (not shown in this particular image) that are stitched to the body of the outfit in a uniform pattern. The decorative yoke is ideal for showcasing taniko designs that are significant or meaningful to the group. In the same way pari are created for the more traditional costume, the yoke, and indeed, even the shoulder straps may be woven, cross-stitched or decorated in an appropriate taniko design. Worn as a long dress, this style of costume is obviously a women's garment - male members of the cultural group wear normal costume as described above. Tipare on women, neck and ear ornaments and feathers in the hair may also be included.

FIBRES AND DYES

In past times, colouring the prepared harakeke (flax Phormium tenax) fibres to weave into kakahu and other items of clothing incorporated natural dyes that were rendered from specific plants or trees or from the minerals found in certain types of mud. Colours were limited to black (from mud with a high iron content found in swampy areas ), yellow (which came from Raurekau bark) and reddish-brown (from Tanekaha bark) while other fibres were left natural. These dyes were used for hundreds of years but after European contact, early 19th century traders brought woollen goods which were often unravelled to obtain yarn. Some yarns were oversewn onto existing taniko borders on kakahu and rapaki and eventually some yarns were used in the weaving process. Colours included blue, green, purple, turquoise, scarlet, etc, many of them being very dark shades. This practice did not last long because the yarns tended to wear out and break faster than the harakeke materials, so yarn was eventually abandoned as a weaving material.

With the convenience and availability of modern fibres and synthetic (chemical) dyes, in the latter half of the 20th century costumes became more brightly coloured and, based on the original plant-based dyes used in taniko designs, the red-white-black colour combination was established as traditional. Very attractive green, white and black designs, often re-interpretations of older designs originally created in the red-white-black combination, began appearing on pari, tipare and tatua, as well as on kakahu. Some presentations which I have attended include a change of pari, tipare and tatua. Costumes using traditional colours may be worn, for example, in the first half of the performance, and after a short intermission the group may continue their presentation wearing costumes with the same taniko design but which might include other colours.

School groups now also compete in kapa haka competitions around the country in costumes that include their school colours. More recently, i.e. the 1990s and into the 21st century, blue, in it's many hues, tints and shades, began to emerge as a dominant costume colour, often in combination with either white, black or yellow, or using all 4 colours together. Used with care and attention to costume detail, this could be considered another form of costume evolution, even though the colour blue did not appear in indigenous textiles until post-European contact.

INTO THE FUTURE

Taniko designs will endure on Maori costume, whether traditionally woven or interpreted through some other creative process, and certainly on kakahu. One hundred and fifty years ago weavers included non-natural coloured wool yarns brought to New Zealand by traders but weavers today seem to retrospectively prefer dyed fibres that reflect the original mud and plant-based dye colours of reddish-brown, yellow, black and natural. While patterns have also changed in style many old Classical period motifs are still being used, or have been adapted. The weaver's sense of harmony and balance in the placement of design elements and the use of colour gives new life to old motifs while creating new designs that will ensure the survival of taniko weaving as both an adornment for kakahu, and as a stand-alone textile in the manufacture of modern-day items.

Copyright 1999 - 2006(�), Judy Shorten

Original page created 1999. Most recent update - June, 2006